Past

Before I ever studied design, I knew its emotional power. I experienced this kind of clarity during my trip with the Peter Pan Vakantieclub (Figure 12), a foundation that organizes holidays for young people with chronic illnesses. I joined a trip with other youth living with neuromuscular disorders. We were among peers, and for once, we didn’t need to explain or hide anything. There was no pressure to keep up, no judgment, no shame. That space allowed me to feel fully myself, free from the weight of performance. For the first time, I wasn’t planning for my future or trying to meet expectations, I was just being. And that experience gave me the mental reset I desperately needed. I returned knowing what I wanted to study, and with the focus and energy to pursue it. That trip showed me that true rest, emotional rest, comes not from withdrawal, but from full immersion in something safe, meaningful, and shared. That is the kind of design I want to create for others.

My first design intervention was the film Doorspelen?! (Figure 13), which we presented in schools. It dealt with peer pressure, and watching students engage, reflect, and share was a turning point. I realized then that design could spark conversation and emotional awareness, not just deliver outcomes.

In Year 1 at TU/e, I approached everything like a checklist. I was excited and ambitious, but I didn’t yet understand how to connect the program to my own values. I created visually rich work (like the fantasy-inspired model in CBL2 (Figure 14)) but treated each project as an isolated task. Reflection felt abstract, and I rarely articulated what I was learning.

In team projects, I often hid my limitations. I contributed visually, but didn’t communicate when I needed support. Looking back, I see how that limited both my impact and my learning. My design process was productive, but not reflective.

Failing my PI&V portfolio forced me to rethink everything. I realized that design isn’t just about what you make, it’s about how you grow through making. The feedback I received pointed to a lack of coherence, depth, and personal connection. It wasn’t just my structure that needed work, it was my story.

So, I changed my approach. I started sharing my boundaries with teammates. I built rest into my schedule. And I redefined what success looked like, not as doing everything, but as doing things with meaning. I also started setting goals more clearly and tracking them. My goal this year was to reconnect motivation, understand the educational structure, and make it work for me. That shift in mindset created space to grow, not just as a designer, but as a person.

Figure 16 – Decor Animal farm without light for Cresendo

Figure 17 – Decor Animal farm with light for Cresendo

Figure 18 – Game for getting to know someone a “kletspot” for Selene

Figure 19 – Personalized Pin for CBL 3

Figure 20 – A statonairy rigged Ignis for CBL 2

Figure 21 – A dynamic rigged Ignis for CBL 2

Figure 22 – The atmosphere is created by using the lighting for the shadows in the image for CBL 3 MySupportPin

Figure 15 – Creativity and Aesthetics final product “Puffaroo”

Present

In Year 2, I stopped treating the educational framework as a checklist and started shaping it to fit my values and energy. Conversations with peers, coaches, and professionals like P&P Projects helped me see it as a flexible guide rather than a fixed path.

Understanding the rubric was especially challenging due to my dyslexia. To address this, I developed a support system using ChatGPT, which helped me rephrase criteria and generate meaningful reflection prompts. This gave me clarity and made feedback feel actionable. I also adjusted how I learn. By reducing my course load, I created space to go deeper. I began setting intentional goals, like learning to work with the framework, maintaining motivation, and building a sustainable rhythm. The result wasn’t just better performance, but more purposeful growth. This shift is most clearly visible in how I engaged with the expertise areas.

Across the expertise areas, my learning in Year 2 became more layered, intentional, and personally relevant. I stopped treating each area as a separate checkbox and started to see how they overlap and strengthen each other. My choices became more grounded in who I am and how I want to design.

In Creativity & Aesthetics, I discovered how experience can be the design itself. Aesthetics became not just about making something “look good,” but about shaping emotional rhythm. In Puffaroo (Figure 15), I focused on tactile interaction, theatrical softness, and subtle movement. But the most eye-opening lesson came through working on the Crescendo décor (Figure 16 & 17), where I began to understand the emotional power of light. Something as simple as color transitions or directional light became a storytelling element. This inspired me to incorporate layered lighting and symbolism in my models, which I’ll be carrying into the updated set. Visually, I grew stronger in Illustrator, learning to work with different aesthetic styles depending on the context, playful for games (Figure 18), clear for plans, and expressive for mood. From my background in animation and theatre, I brought the mindset that small details matter. That extra effort, adding just one more light, one more layer, can be what turns a good design into a memorable one.

In User & Society, I shifted from designing “about” users to designing with them. Working with autistic students in CBL3 taught me that empathy must be earned. We designed user tests that allowed participants to explore the product in a safe, paced environment. One of the strongest insights was that they wanted personalisation, not just something that looked friendly, but something that felt like theirs. That realisation shaped the MySupportPin (Figure 19), a design that could be modified to suit the user. I now understand that co-design isn’t only about inclusion, it’s about giving up control. It’s about listening not just to needs, but to preferences, anxieties, and identities. That requires being present, asking without assumptions, and adjusting accordingly.

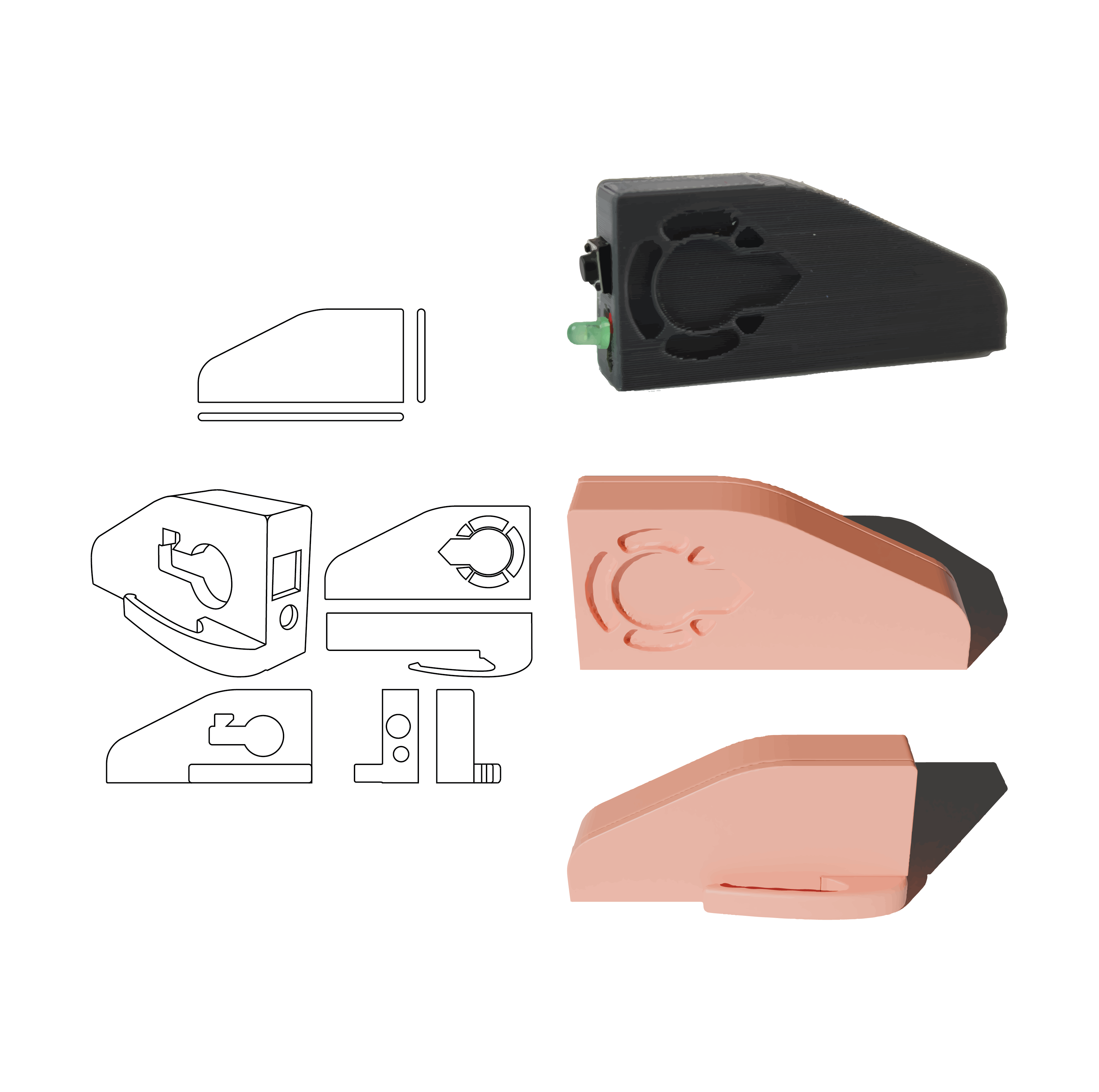

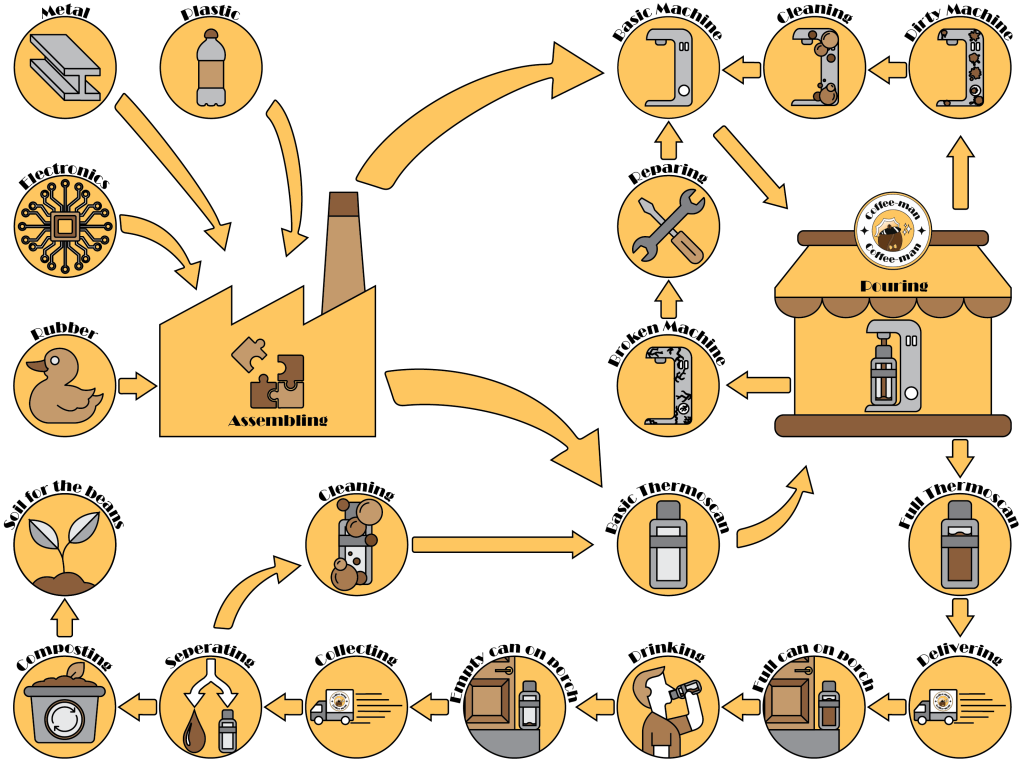

In Technology & Realization, my process became more adaptive. Because of my physical limitations, I leaned heavily on digital tools, but instead of seeing this as a constraint, I made it a strength. In Blender, I learned how to rig models for animation (Figure 20 & 21) and use lighting to create atmosphere in renders (Figure 22). In Illustrator, I expanded into new formats: playing cards (Figure 23), system diagrams (Figure 24), and construction drawings [Download 2]. These tools allowed me to explore more styles and gradually build my own visual voice. I also became more aware of error margins and physical tolerances. In 3D printing and laser cutting, I started accounting for the difference between theoretical dimensions and real-world material behaviour. Knowing when to allow extra space, or when laser width would distort alignment, gave me more control and confidence when moving from concept to fabrication.

In Math, Data & Computing, I moved from passive understanding to applied exploration. For the first time, I had the mental space to truly engage with technical content. In CBL3, I analysed qualitative user feedback, splitting responses, grouping patterns, and looking for emerging themes. I used Python in Jupyter Notebook to organise and explore the data. What surprised me most was how this connected to emotional intelligence: spotting a subtle trend in wording or tone helped me understand how people were experiencing our design. Even without a direct design decision linked to this, it changed how I think. Data doesn’t just support ideas; it can reveal undercurrents. It made me realise I can use analysis not only for validation, but as a source of empathy.

In Business & Entrepreneurship, my thinking became more context sensitive. Working with Crescendo taught me that communication isn’t one-size-fits-all. What you say to a builder is not what you say to a director or a sponsor. I learned to translate my vision into different “languages” depending on who I was talking to. I also saw how poor planning affects production, again, our process ran late. That’s why we’ve decided to start earlier next year, learning from experience to set more realistic timelines. During my work for #WijDoenHetAnders, I had the opportunity to pitch an idea in a spontaneous conversation with a TU/e trainer. It showed promise, but I hadn’t yet thought through the value proposition. That experience taught me the importance of defining expectations early: What problem are we solving? What makes our offer unique? How does this benefit the stakeholder? I now see commercial thinking not as a threat to creativity, but as a tool to open doors, if used ethically and intentionally.

Together, these developments paint a clearer picture of who I’m becoming as a designer: someone who connects conceptual thinking with practical strategy, emotional design with inclusive collaboration, and self-awareness with professional confidence. The expertise areas are no longer abstract terms to me, they are different lenses through which I can better understand, build, and communicate my work.

Figure 23 – Playing cards for 30 seconds #WijDoenHetAnders

Figure 24 – Systemic drawings for the circularity module of sustainable design

Growth as a designer

Year 2 was not only a year of integration, but of conscious transformation. For the first time, I shifted from simply participating in projects to actively shaping how I wanted to grow. This shift wasn’t abstract, it happened in the small, practical decisions I made reducing my workload to protect energy, choosing courses with emotional relevance, and reflecting regularly on my process rather than just the output.

One of the most defining aspects of my growth has been learning how to set boundaries, both personal and creative. I deliberately scaled down my academic load, not because I couldn’t handle more, but because I realized that doing less allowed me to go deeper. It gave me space to experiment, to make mistakes, and to find joy in designing again. Through this, I developed a more sustainable way of working, one that respects both my capabilities and my limits.

Another key shift was in how I see design itself. In the past, I focused on expression and output. Now, I understand that design is a conversation, between intention and execution, between user and creator, and between vision and feasibility. I learned to reflect in motion: to take time within a project to ask myself, “What am I really doing here?” and “Does this still align with my values?”

Collaboration also became more meaningful. I used to think teamwork was about task division. Now I see it as shared authorship. In CBL3 and multidisciplinary projects, I learned to communicate more clearly about my process, my limits, and my ideas. I asked emotional questions during brainstorms, questions like “How should this feel?” and “What experience are we actually trying to create?” This created alignment within the group and shaped more thoughtful outcomes.

I also became more confident in what makes me unique. My background in theatre, my lived experience with disability, and my focus on emotion are no longer side notes, they are the foundation of my identity. I now frame them as strengths when I present work. I don’t just say what I designed; I explain why it mattered, and how my perspective influenced it.

Perhaps most importantly, I began designing for myself again. Not just to meet learning goals, but to answer real questions I had about the world, about experience, and about care. This personal investment made my designs richer and more resonant, not just for users, but for me.

Future

Looking ahead, I see the coming years as an open framework, not a fixed path. My goal isn’t just to master tools or complete projects, but to deepen the kind of designer I’m becoming someone who crafts emotionally resonant, immersive experiences that offer people space to reflect, breathe, and reconnect.

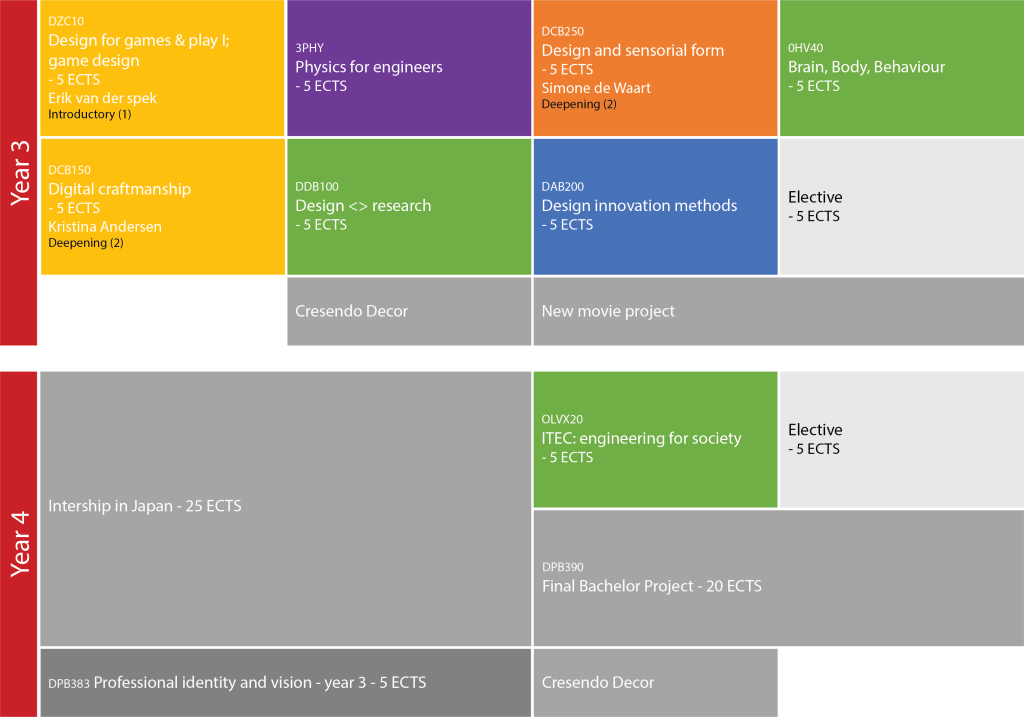

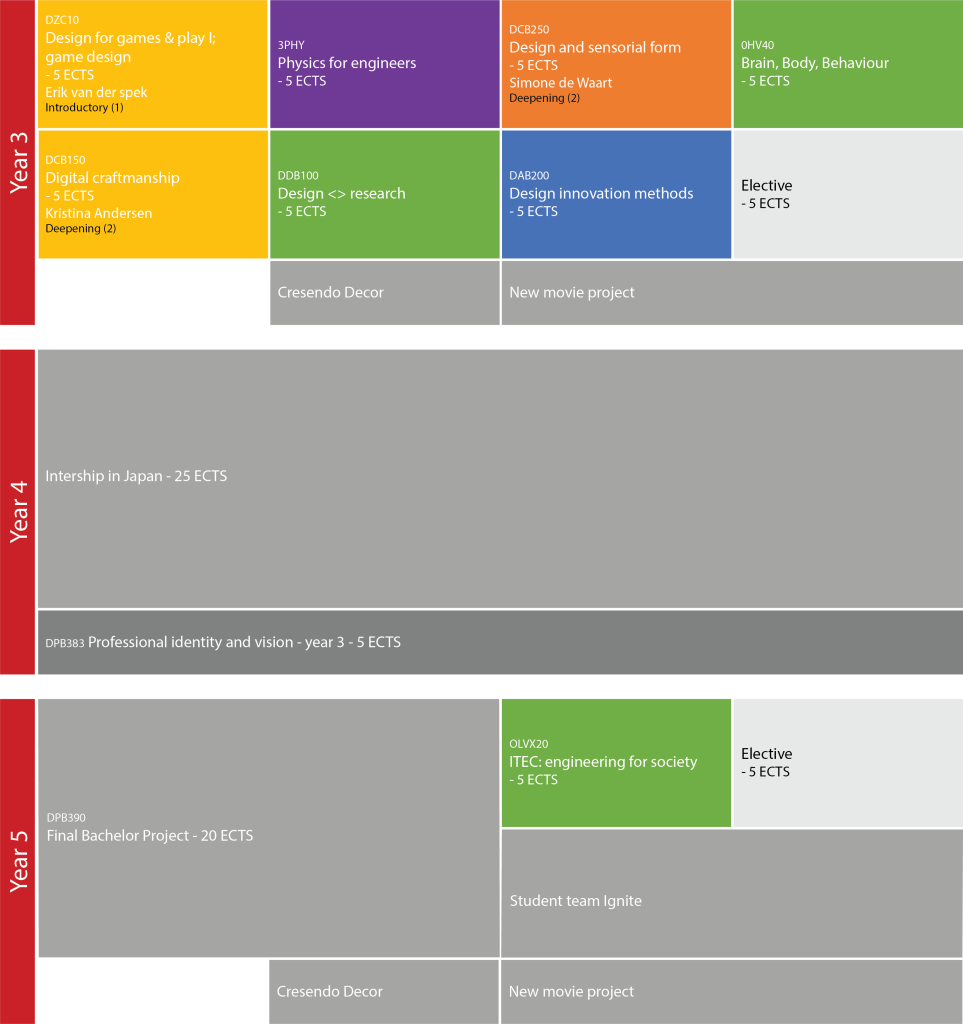

In Year 3, I’m intentionally building on what I’ve discovered in Year 2. My course choices are no longer based on what seems expected or strategic, they’re based on what supports my identity. Courses like Designing for Games and Play, Design and Sensorial Form, and Brain, Body & Behaviour help me understand how people perceive, feel, and engage with design. These are not just technical or theoretical; they’re emotional tools that help me translate vision into interaction.

Digital Craftsmanship supports my way of working. Since I rely on digital tools to realize physical designs (due to energy limits), this course helps me prototype smarter, more accessibly, and more precisely. It’s part of my long-term goal to develop a design workflow that’s sustainable both in production and in health.

Parallel to my coursework, I’m working on two major projects. First, the ongoing Crescendo theatre décor project, where I continue experimenting with emotional atmosphere and storytelling through space. Second, a new film project that combines narrative layering and social engagement, designed not only for entertainment, but for reflection and connection.

Importantly, I’ve left one elective open. This isn’t indecision, it’s part of my strategy. I want to stay flexible and choose that course based on what I learn about myself in the coming months. This reflects how I now work: adaptively, responsively, and with reflection at the core.

In Year 4, I want to apply everything I’ve learned in the real world. I hope to do an internship abroad, ideally in Japan, in a context focused on immersive design, whether in exhibitions, themed experiences, or entertainment. More than the location, I’m seeking new cultural rhythms, ways of thinking, and emotional cues. I believe that stepping outside my own environment will stretch my design perspective and deepen my empathy.

My Final Bachelor Project will likely centre around a dark ride or other immersive spatial experience. I want to combine my skills in storytelling, emotional design, spatial rhythm, and digital prototyping into one integrated project. Whether it becomes a collaboration with P&P Projects or remains self-initiated, my main criterion is that it expresses who I am and pushes me one step further.

Finally, I’m leaving space for change. I know my vision and physical possibilities may change (Figure 26 & 27). I welcome that. That’s why, in parallel with everything else, I’m staying reflective writing, gathering inspiration, having conversations. These aren’t side activities. They’re part of my design process.

Rather than trying to control my future, I now see it as a co-creation, between me, my collaborators, my experiences, and my evolving sense of what design can do. For those who wish to explore my plans in more detail, including the reasoning behind each course choice, project theme, and adaptability strategy, I’ve outlined everything in my Personal Development Plan [Download 1].

Figure 20 – Planning of upcoming years assuming that my physical health will allow it

Figure 21 – Planning of upcoming years if my physical health will work against me